Unintended distractions impede communication

My work is about improving the flow of information. To communicate ideas successfully to other people you need to get rid of distractions because they will irritate your audience and divert attention from your message. Errors of fact, errors in grammar and punctuation, inconsistencies in style and infelicities in appearance can all distract your readers.

Strategies for minimising errors

There are three distinct approaches to the problem. They are not alternatives: you need to do them all.

- Check finished work so as to find the errors in it

- For each error that you know exists, decide what to do about it

- Improve working methods so as to reduce the occurrence of errors

The process of finding errors

To find errors that might impede communication you have to think about how the recipient might misunderstand your meaning. You have to look with fresh eyes at the draft publication, examining it for errors, ambiguities and opacities that might cause a reader to waste time trying to fit incorrect but plausible possible meanings to it, or to start thinking about some other aspect of the material that doesn’t relate to the ideas you are trying to convey.

I am excited by the work of identifying errors and infelicities, whether they occur in text, in pictures or in computer source code. I enjoy the mental process involved: the imaginative effort that it takes to put oneself into the position of the reader (or the computer), lacking the background knowledge that would resolve ambiguities, and then to see whether the text still makes sense. I also enjoy the state of total immersion in the task, which is absolutely necessary for this work of polishing and improving – it can’t be done if you have any part of your mind on something else.

It happens that I am rather good at this. As a reader I am very easily distracted and misled by errors in text, even those that many other readers don’t see. They irritate me and make my mind wander away from what the author is trying to say. It can be a real annoyance when I’m reading for information, but this propensity is exactly what gives me the ability to do this sort of work successfully.

See my art pages to understand the connection between the way I think about making (or editing) pictures and the way I edit text or software. There are some surprising parallels here.

Deciding whether errors are worth correcting

To make a thoroughly professional job of preparing a publication you have to do something that is more difficult, and less satisfying, than simply finding the errors – but absolutely necessary. You have to decide, for each error you have found, whether it is worth fixing: whether the risk incurred by making the change is greater than the risk of harm being done by leaving the error in. The hardest thing about this work is having to make a decision to leave a known error uncorrected.

To a person inexperienced in the field it is very hard to see why this should ever be necessary. It is very difficult to persuade authors of text that a correction, although clearly desirable, simply can’t be done – even if the book hasn’t been printed yet. Similarly, restraining junior programmers, especially very able ones, from fixing bugs in software is very difficult. The most important task for the professional handler of errors is to make the right decision about each error and to persuade everyone else involved to accept it.

These are the things we have to weigh when deciding whether to correct an error:

- How much will the correction cost? How much work will have to be re-done as a consequence of the change? How much delay will be caused? What is the cost of the delay?

- How much harm would the uncorrected error cause? Can the user or reader, although perhaps annoyed by it, work around it without serious inconvenience? How much will the presence of the error harm our reputation or weaken the case we are trying to make?

- What new errors do we risk introducing in our efforts to correct this one? Are we likely to notice them in the time we have left to re-check the final result? What is the risk that they turn out to be worse – more harmful – errors than this one?

In the software industry this decision process is commonly referred to by a term borrowed from the field of emergency medicine: triage. It is usually the responsibility of a release manager working in conjunction with a product manager. I have done a lot of work in this area.

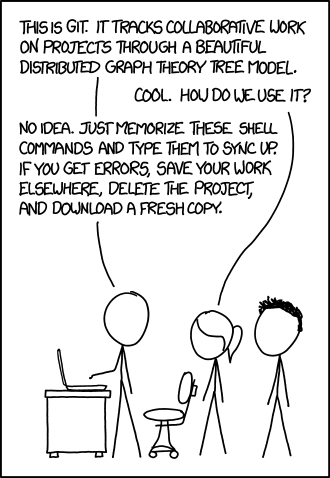

Preventing errors from occurring

Dealing with errors in a publication is in some ways analogous to the job of testing and debugging a software system. To communicate successfully with a computer you need to avoid making errors of logic that will mislead it. This is not very different, conceptually, from the process of eliminating errors in the text and layout of publications to prevent them misleading human readers. As a software engineer I spent a lot of my time worrying about errors and devising ways of preventing them appearing, and I became an advocate for the use of configuration management systems, portable programming techniques and coding standards long before the need for these things was generally taken for granted. I learned some valuable lessons from this, many of which I believe are applicable in publishing also.

Since I began my career in the software industry in the early 1980s I have seen huge advances in the understanding of error prevention and in the general acceptance of systems and working practices that help with it. In the 1980s and early 1990s some respected software developers would argue passionately against the use of a source code control system on the grounds that it stifled their creativity, or object to running nightly builds and automated tests on the grounds that they wasted resources. This kind of thing is much less common today. I believe the same kind of change will eventually happen in the publishing industry also.